Knowledge is power, and with cancer, it can make the difference between life and death. It’s estimated there are over a million LGBTQIA+ cancer survivors. And the numbers may actually be much higher as only a quarter (24%) of National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Oncology Research Program practice groups collect information on sexual orientation, and only 10% collect information on gender identity.

Cancer risks can increase as you get older. There’s no better time to get informed about the risks, screenings, and prevention methods than during the menopause journey. Embrace a greater sense of LGBTQIA+ well-being for today and the future.

LGBTQIA+ cancer risks

Cancer is a condition of which LGBTQIA+ people should be aware as an area of health disparity, disproportionately impacting this community.

Disparities can exist because of socioeconomic factors and health behaviors. For the LGBTQIA+ community, certain factors may increase the likelihood of cancer, including:

- the use of tobacco and/or alcohol

- not having biological children or having them later in life

- higher rates of obesity

- diets high in fat

In addition, there are other factors like:

- bias, discrimination, and anti-LGBTQIA+ intolerance

- lack of access to healthcare practitioners with the training and expertise to address what can be unique needs in the LGBTQIA+ community

Cancer is one condition for which health disparity exists. In our prescription for health series, we talk about others.

Singling out cancer is essential because there are so many types for which the LGBTQIA+ community may be at increased risk:

- Cervical

- Ovarian

- Breast

- Endometrial

- Anal

- Colorectal

- Prostate

- Lung

We break down the risk factors and treatment guidelines for better health. Remember, knowledge is power.

In general, cervical, ovarian, and breast cancer risks are higher

for lesbian and bisexual women.

Cervical cancer

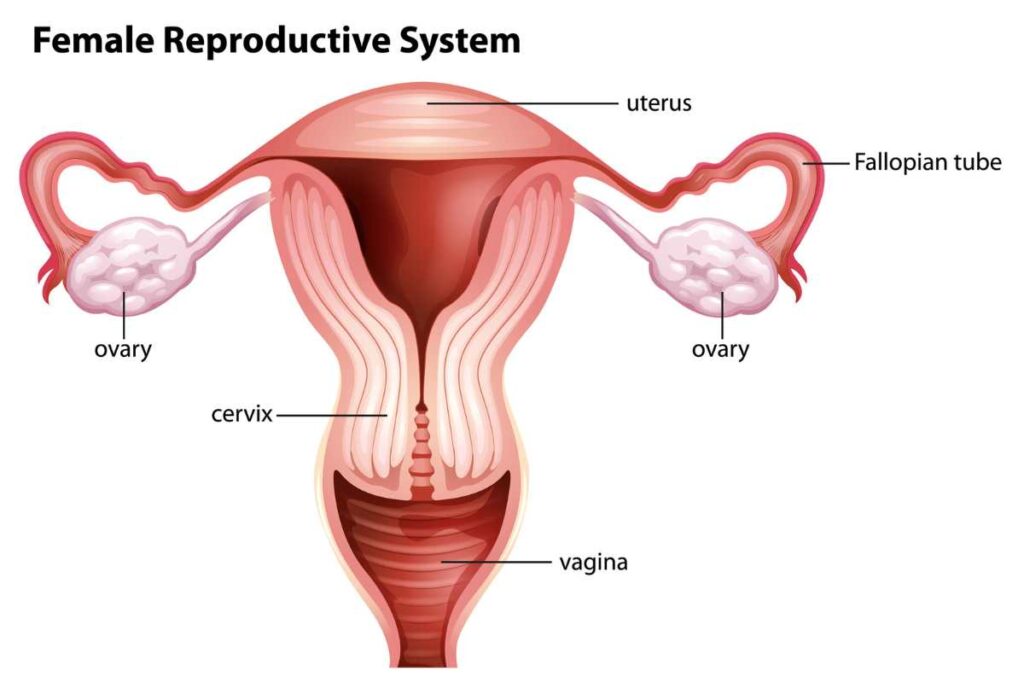

Cervical cancer, the fourth most common cancer in women, develops in the cervix. If diagnosed and treated early, cervical cancer is often successfully managed.

Symptoms and signs of cervical cancer include:

- Vaginal bleeding after sex or during menopause.

- Unusual discharge that has a strong odor and watery texture.

- Pain in the pelvis, back, or abdomen.

- Painful urination or blood in urine.

- Fatigue

Have you been screened for HPV?

HPV (human papillomavirus) is an STI (sexually transmitted infection) that is the most common cause of cervical cancer. It can also cause genital warts and other types of cancers – oropharyngeal (mouth and throat), vaginal, vulvar, and penile cancers).

A test for HPV can be performed at the same time as a Pap smear.

Most people never develop symptoms and find out when they develop cancer or have an abnormal Pap test.

In 9 out of 10 cases, HPV clears within 2 years without issue.

Risk factors

LGBTQIA+ populations are also more likely to smoke or have HIV, both of which are additional risk factors for cervical cancer.

Other risk factors of which you will want to be aware include:

- Being overweight

- Having a chlamydia infection

- Family history of cervical cancer

- A diet low in fruits and veggies

- Long-term use of BCPs (birth control pills)

- Having 3 or more full-term pregnancies

- A sexual history which includes becoming sexually active younger than age 18

- Having multiple sexual partners

- Having a partner who is high risk for HPV

- Exposure to DES (diethylstilbestrol)

After a period of decline, a recent study indicates that the incidence (number of new diagnoses) and mortality rates for cervical cancer in non-Hispanic white women who live in low-income counties is on the rise.

The 5-year survival rate for cervical cancer is 91% when caught early, so talk to your doctor about regular screenings and the HPV vaccine based on guidelines and your particular situation.

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer develops in the ovaries, which are located on each side of the uterus.

Possible signs and symptoms include:

- abdominal bloating and feeling full quickly when eating

- frequent urination

- pain or discomfort in the pelvis

- constipation

- unintentional weight loss

- back pain

- fatigue

For all people with ovaries, ovarian cancer risk rises with age.

Pay attention to your body and any changes you notice, as there is no reliable test for ovarian cancer screening.

Most ovarian cancer diagnoses are made in advanced stages - Stage III or IV - of the disease.

It’s also more likely in women who haven’t been pregnant or who did not breastfeed their children, especially before the age of 30. And, as previously noted, lesbians are less likely than heterosexual women to have biological children.

Other risk factors include:

- Obesity

- A family history of ovarian cancer.

- Having a personal history of breast cancer.

- Having a personal history of colorectal cancer.

- Use of in-vitro fertilization (IVF) for infertility issues

- Having the BRCA gene (which increases the risk up to 50% depending on the specific

- Smoking

- A history of family cancer syndromes such as hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Breast cancer

In the U.S., breast cancer is the most common cancer in women+ after skin cancer.

As its name suggests, breast cancer is a cancerous growth in the breast. Its most common symptom is a new lump in the breast, although most breast lumps are not cancerous. Though often painless with irregular edges, they can be tender or painful.

1 in 8 women+ will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime.

It's the second-leading cause of death after lung cancer.

The risk of recurrence is 3 times higher for LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Other signs and symptoms can include:

- Breast or nipple pain

- Nipple retraction (turning inwards) or discharge

- Skins changes on the breast such as reddening, thickening, dryness or flaking

- Breast swelling (full or partial)

- Swollen lymph nodes

In addition to the risk factors previously identified in the article, LGBTQIA+ individuals may also face delays in diagnosis. For example, transgender men who have not undergone top surgery often don’t receive preventive care such as mammograms. Studies also show that lesbian women are less likely to get breast cancer screening exams.

These gaps in care may contribute to the three times higher risk of faster breast cancer recurrence LGBTQIA+ people experience compared to cisgender, heterosexual people.

If you notice something irregular, talk to your doctor and get regular screening, which usually means mammograms in most people.

Endometrial (uterine) cancer

In addition to being the most common GYN cancer in the U.S., the endometrial cancer (also known as uterine cancer or cancer of the womb) rate is also rising, especially in Black and younger Hispanic women+.

Additional health disparities for women of color and those in the LGBTQIA+ community can also contribute to an increased risk.

Endometrial cancer is most often seen during the post-menopause stage of life.

Possible signs and symptoms include:

- Bleeding between periods or after menopause: more than 90% of people diagnosed with endometrial cancer report abnormal vaginal bleeding

- Painful urination

- Pain during penetrative sex

- Pelvic pain

- Lumps or mass in the pelvic area

Several factors increase the risk of developing endometrial cancer. They include:

- Being a Black woman (more likely to have more aggressive forms of cancer and the racial group most likely to die from it)

- Having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Being overweight/obese

- Having diabetes

- Family history of Lynch Syndrome (genetic mutation that increases the risk of colon cancer, breast cancer, or ovarian cancer)

- Personal history of breast or ovarian cancers

- Using estrogen-only hormone therapy if your uterus is still intact

- Starting menstrual cycles at an age younger than 12

- Entering menopause later than the typical age (51 years old in the U.S. but it may be earlier in women of color)

- History of taking tamoxifen

- Prior pelvic radiation

- A high-fat diet

- Being infertile or never having been pregnant

There are also factors that lower the risk of endometrial cancer, like:

- hormonal birth control

- the use of an IUD

- being physically active

- pregnancy

Endometrial risk for the LGBTQIA+ community

Members of the LGBTQIA+ community are at greater risk of several of the conditions which increase the risk of endometrial cancer. Those include being overweight/obese, having type 2 diabetes, and having breast and ovarian cancer.

Also, the factors contributing to a lower risk of endometrial cancer are less likely. An LGBTQIA+ person has a lower likelihood of using birth control, and lesbians are 50% less likely to become pregnant/have a baby. Both birth control and pregnancy can lower the risk of endometrial cancer.

Additional disparities exist among Black women and other women of color, including those who are LGBTQIA+ community members. For example:

Diagnosis and Care

- Being Black or Hispanic increases the risk of being diagnosed at a more advanced stage of cancer.

- Black women are less likely to undergo diagnostic procedures that align with medical guidelines.

- Black, Hispanic, and Native American/Alaska Native women are less likely to receive treatment that adheres to clinical guidelines.

Treatment

- Black and Hispanic women are less likely to receive lymph node dissection and sampling, definitive surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and surgery, especially minimally-invasive surgery (laparoscopic surgery).

- What’s more, these findings apply even though Black women are more likely to receive care from GYN oncologists, high-volume uterine cancer surgeons, and at National Cancer Institute Centers!

Another possible reason why gynecological cancer rates are higher in LGBTQIA+ populations? Across obstetrics and gynecology residency programs, standardized training is lacking for LGBTQIA+ populations.

We want to give you the tools you need to find inclusive partners. You can find a list of cancer providers at the end of this article and links to other lists provided in the LGBTQIA+ series of articles.

Anal cancer

While cancer of the anus is rare in the general population (2 of 100,000 people per year), the incidence is much higher for people assigned male at birth having sex with men (40-80 of 100,000 people).

It’s important to note that while it’s most associated with gay men, people assigned female at birth can also develop anal cancer.

It’s often caused by the same HPV strains that cause cervical cancer. It also develops slowly like cervical cancer.

Possible signs and symptoms include:

- Mucus or bleeding from the bottom

- Itching and pain around the anus

- Lumps in and around the anus

- Bowel incontinence

- Looser stools

A push is being made to make an anal pap test (a moistened cotton swab that is used to collect cells from the anal canal) more routine, especially for high-risk populations.

Colorectal cancer

Sometimes called colon cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC) is cancer of the colon or rectum (the passage that connects the colon to the anus). Because colon cancer most often begins with abnormal growths called polyps, early screening is helpful to remove the polyps before they become cancerous.

Disturbingly, the incidence of colon cancer in those who are younger than 50 has been on the rise and now accounts for 10% of new diagnoses of colon cancer and 25% of new rectal cancers. This trend has been noted more significantly in males than in females.

Due to risk factors like obesity and smoking, the LGBTQIA+ community is disproportionately impacted by CRC.

Though symptoms often don’t appear in early stages, they can include:

- Rectal bleeding or bloody stool

- Abdominal pain or discomfort

- A feeling of incomplete bowel movements

- Fatigue

- Unintentional weight loss

- Change in bowel habits (frequency, size, shape)

- Diarrhea and/or constipation

Screening makes a difference! The 5-year survival rate for those diagnosed in Stage I is 91%.

Current guidelines recommend starting screening at age 45 unless you have a risk factor that increases the chances of developing CRC.

Although colonoscopy remains the “gold standard” for CRC screening, other options exist, including stool testing for blood and/or DNA changes.

Seek guidance from a healthcare professional to determine the age and best screening test for your particular situation and take advantage of the opportunity to save your life.

Prostate cancer

While women+ do not have a prostate, this cancer is of concern to transgender women. Prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in males+.

Being African American and/or having a family history of prostate cancer increases your risk of developing it.

For transgender women, your risk may actually be lower if you’re on a hormone regimen.

Thus far, it appears that bisexual males are not at an increased risk of prostate cancer unless they’ve had 20 or more sexual partners.

Overall, though, research is lacking in the LGTBQIA+ community compared to the cisgender, heterosexual population. Studies are even more limited for specific cancers.

It’s of concern because most people with prostate cancer do not have symptoms, and there is some controversy regarding screening because even though men and trans women may develop prostate cancer, it may not be the ultimate cause of a person’s death.

Let’s talk about symptoms that can indicate prostate cancer. But understand that sometimes there are no symptoms.

- Problems with urination – difficulty starting, weak flow, pain or burning, frequent urination, especially at night, problems with emptying the bladder

- Blood in the urine

- Blood in semen, painful ejaculation

- Persistent pain in the back, hips, or pelvis

For those at high risk, screening can help you catch things early. If prostate cancer is caught in Stage 1, the 5-year survival rate is almost 100%.

The major ways to check for potential cancer are:

- A PSA (prostate-specific antigen) blood test.

- A rectal exam, during which your healthcare practitioner may feel nodules or a hard consistency.

Lung cancer

More LGBTQIA+ people use tobacco than their heterosexual counterparts, thereby increasing their risk for lung cancer. That said, it can also occur in those who haven’t smoked.

Beginning in the lungs, lung cancer is the world’s leading cause of cancer death—and the number one cause of preventable disease and death.

In most cases, lung cancer does not cause symptoms in the early stages. But when it does, some signs and symptoms are:

- An unrelenting cough

- Chest pain

- Coughing up blood

In later stages, there may be signs the cancer has spread like headaches, bone pain, a hoarse and/or scratchy voice, and unintentional weight loss.

Smoking is the most common cause of lung cancer. Speak with your healthcare practitioner to find out if you should go for lung cancer screening with a low-dose CT scan. See “Saved By the Scan,” a resource by the American Lung Association to help high-risk individuals get screened.

Transgender cancer guidelines

Unfortunately, with the exception of breast cancer screening guidelines from the American College of Radiology for transgender people, there are currently no cancer screening guidelines specific to the transgender community.

Until they are developed, transgender individuals are generally advised to adhere to the same applicable cancer screening guidelines as the cis gender population, e.g., Pap smear and HPV testing in the case of cervical cancer.

Finding inclusive cancer care

Several organizations are committed to inclusive health care and provide directoriess for LGBTQIA+ people.

For cancer specifically, the National LGBT Cancer Network provides educational information about cancer risks and prevention as well as support groups. A National LGBT Cancer Network study found support groups specific to LGBTQIA+ people was the top request among LGBTQIA+ cancer survivors.

The network offers free virtual cancer peer-support groups 3 times a week. Sign up for a National LGBT Cancer Network virtual cancer support group session.

The organization also curates the latest information on other supportive groups like private and public groups for support and websites focused on the lived experience for LGBTQIA+ people with cancer.

In addition, you can reach out to an LGBTQIA+ inclusive provider. We identify these in our series of LGBTQIA+ articles.

Resources

National LGBT Cancer Information | National LGBT Cancer Network

Cervical Cancer | World Health Organization

Cervical Cancer Symptoms | National Cancer Institute

HPV and Cancer | National Cancer Institute

Cervical Cancer Basics | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

About Genital HPV Infection | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Tips From Former Smokers®: LGBTQ+ People | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

How HIV Impacts LGBTQ+ People | Human Rights Campaign

LGBTQ+ | Drugwatch

Ovarian Cancer | Mayo Clinic

Ovarian Cancer | Drugwatch

Ovarian Cancer Risk Factors | American Cancer Society

Cancer Facts for Lesbian and Bisexual Women | American Cancer Society

Breast Cancer Signs and Symptoms | American Cancer Society

LGBTQ People with Breast Cancer Have Delayed Diagnoses, Higher Recurrent Rates | Breastcancer.org

Sterling J, Garcia MM. Cancer screening in the transgender population: a review of current guidelines, best practices, and a proposed care model. Transl Androl Urol. 2020 Dec;9(6):2771-2785. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-954. PMID: 33457249; PMCID: PMC7807311.

10 Things Lesbians Should Discuss | GLMA Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ+ Equity

Eckhert E, Lansinger O, Ritter V, et al. Breast Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes of Patients From Sex and Gender Minority Groups. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(4):473–480. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7146

Somasegar S, Bashi A, Lang SM, Liao CI, Johnson C, Darcy KM, Tian C, Kapp DS, Chan JK. Trends in Uterine Cancer Mortality in the United States: A 50-Year Population-Based Analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Oct 1;142(4):978-986. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005321. Epub 2023 Sep 7. PMID: 37678887; PMCID: PMC10510793.

Uterine Cancer Deaths Are Rising in the United States, and Are Highest Among Black Women | National Cancer Institute

Endometrial Cancer Prevention (PDQ®) – Patient Version | National Cancer Institute

Uterine Cancer Deaths Are Rising in the United States, And Are Highest Among Black Women | National Cancer Institute

Charlton B, Everett B, Light A, Jones R, Janiak E, Gaskins A, Chavarro J, Moseson H, Sarda V, Austin S. B. Sexual Orientation Differences in Pregnancy and Abortion Across the Lifecourse. Women’s Health Issues. Volume 30, Issue 2, 2020, Pages 65-72, ISSN 1049-3867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.10.007.

Whetstone S, Burke W, Sheth SS, Brooks R, Cavens A, Huber-Keener K, Scott DM, Worly B, Chelmow D. Health Disparities in Uterine Cancer: Report From the Uterine Cancer Evidence Review Conference. Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Apr 1;139(4):645-659. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004710. Epub 2022 Mar 10. PMID: 35272301; PMCID: PMC8936152.

Lee A, Rajagopalan S, Rowland A, Viloria R. Developing an Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency Curriculum for the Care of Gender-Diverse Patients. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2023. Volume 141, Supplement 1, pages 90S-90S(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000931096.06293.f0

Anal Cancer | NHS for England

Sifaki-Pistolla D, Poimenaki V, Fotopoulou I, Saloustros E, Mavroudis D, Vamvakas L, Lionis C. Significant Rise of Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Younger Adults and Strong Determinants: 30 Years Longitudinal Differences between under and over 50s. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Sep 30;14(19):4799. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194799. PMID: 36230718; PMCID: PMC9563745.

What’s Driving the Rise of Colon Cancer in Young Adults? | ASCO Daily News

Colon Cancer | Mayo Clinic

Colorectal Cancer: Statistics | Cancer.Net

Underwood S, Lyratzopoulos G, Saunders CL. Breast, Prostate, Colorectal, and Lung Cancer Incidence and Risk Factors in Women Who Have Sex with Women and Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analysis Using UK Biobank. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Mar 29;15(7):2031. doi: 10.3390/cancers15072031. PMID: 37046692; PMCID: PMC10093616.

Prostate cancer in transgender women | Harvard Health Publishing®

Lung Disease and LGBTQ+ Communities | American Lung Association

Lung Cancer| Mayo Clinic

Who Should Be Screened for Lung Cancer? | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Saved By The Scan | American Lung Association

Cancer Support | National LGBT Cancer Network

Lockhart R, Kamaya A. Patient-Friendly Summary of the ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Transgender Breast Cancer Screening. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2022. Volume 19, Issue 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.10.015

Home | American Cancer Society

Cancer Diagnosis: 11 Tips for Coping | Mayo Clinic

Coping With Cancer as an LGBTQ+ Person | CancerCare®

Resources for LGBTQ+ People with Cancer | Cancer.Net

You may also like...

Transgender Menopause: What to Expect

Transgender menopause can happen. Learn what to expect.

Menopause Pride: The LGBTQIA+ Experience And Where to Find Inclusive Doctors

Every menopause journey is unique. For LGBTQIA+ people there are positives and challenges, like health disparities. Learn how to have menopause pride by knowing what to expect.

Discover the Keys to Better Health: An LGBTQIA+ Prescription for Health

Get a prescription for LGBTQIA+ health during the menopause journey. Know the conditions for which your risk may be greater and the factors that make them more likely.