A woman's health is her capital.

~ Harriet Beecher Stowe

Menopause is a great time to reflect on your overall health and well-being because that foundation can impact symptoms and your health and well-being, as menopause itself can increase your risk for certain chronic conditions. As a Black woman+, your journey may also be impacted by health disparities. Now is the perfect time to learn how to take preventive action to manage symptoms and the consequences of a journey that may be more challenging for Black women+ than for other racial/ethnic groups. Knowing what those are is part of your “prescription for better health.”

Black woman’s prescription for health

Black women+ may have a unique menopause journey compared to their white counterparts, often experiencing menopause earlier, for longer, and with more severe symptoms. Those three factors can impact your health.

In addition, you may experience health disparities, of which menopause may be just one of those disparities.

According to Healthy People 2030, health disparities are

“a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage.”

There can be health disparities based on race/ethnicity, sex, gender/gender identity, age, disability, socioeconomic status, or geographic location.

These differences may be in disease prevalence, complications, access to and quality of care, treatment, and overall health outcomes.

The disparities may also vary based on whether or not a person is born in the U.S.

Like other racial groups, the Black community is diverse. It includes people born in the U.S. as well as the 10% who have immigrated to the U.S.

The 10% of individuals who were born outside the U.S. primarily arrive from the:

- Caribbean (46%)

- African countries (42%)

- Mexico*

- Guyana*

- Honduras*

*12% for the last three countries combined.

And women around the world can have different menopausal symptoms.

Since a woman’s risk for chronic conditions can increase due to the hormonal changes during the menopause journey, it’s important to have a prescription for overall health and well-being.

Let’s examine several health disparities that Black women+ may experience, so you can be on alert for these conditions before, during, and after the menopause journey.

They include:

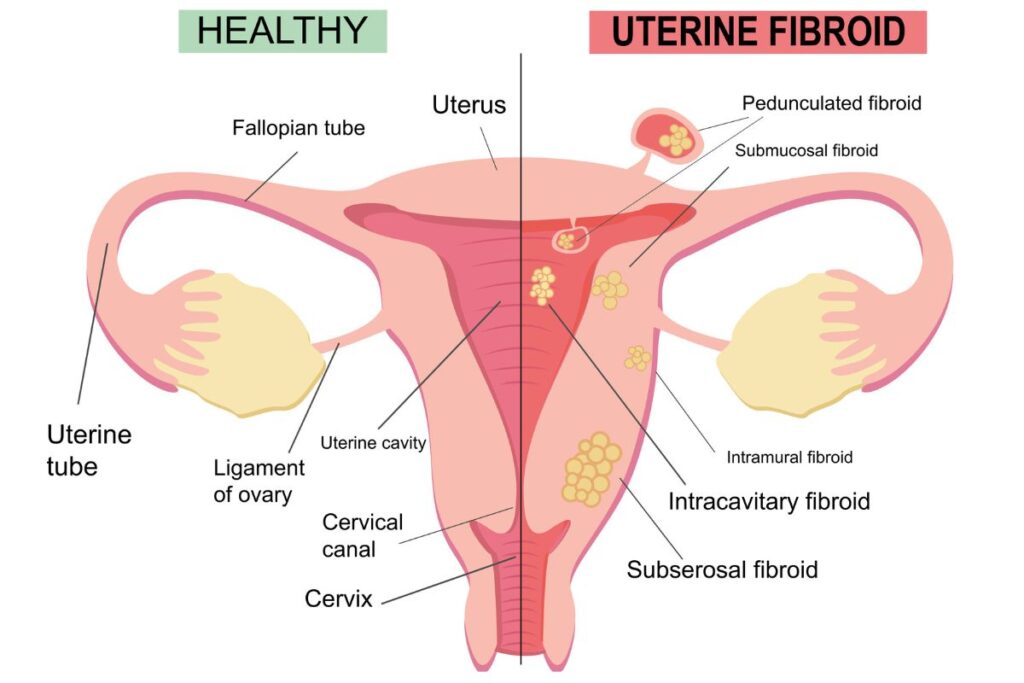

Black women are three times more likely to have fibroids,

have them at an earlier age, have more severe symptoms, have more and larger fibroids, and are more likely to be treated with hysterectomy without exploration of other options than women who are white.

Source: Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation - University of Michigan

Fibroids

Fibroids, also known as leiomyomas, are non-cancerous growths in or on the wall of the uterus.

Up to 77% of women develop fibroids by the time of usual menopause onset (age 51).

Often there are no symptoms, but common signs are heavy bleeding that can be severe enough to cause anemia and abdominal pain or pressure.

For women+ who do have symptoms, those who require treatment are often in perimenopause. One third of the hysterectomies performed in the U.S. are due to fibroids. Having a hysterectomy can put a woman into menopause overnight if her ovaries are removed as part of the procedure.

Additional risk factors are:

- Older age (peak age = 50)

- Obesity

- Family history of uterine fibroids

- High blood pressure

- Never being pregnant

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Genetics

– A higher expression of the von Willebrand factor gene (VWF) has been found in Black women.

– Genetic mutations in the MED12, HMGA2, COL4A5/COL4A6, or FH genes. - Stress (statistically significant risk factor in non-Hispanic Black women)

- Consumption of soy

- Consumption of food additives

Fibroid treatment options

Besides hysterectomy, treatment options include:

- Reducing the risks over which you have control.

- Examples: addressing anemia and a vitamin D deficiency using iron and vitamin D supplementation with guidance from your healthcare practitioner or losing weight.

- If you don’t have any issues (e.g., bleeding, on blood thinners, have kidney disease), taking NSAIDs like ibuprofen and Naprosyn for pain.

- Hormone therapy

- GnRH antagonists – can be used up to 2 years

- GnRH agonists – used preop to reduce the size of fibroids prior to surgery

- Birth control formulations

- Non-surgical procedures

- Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation – shrinks fibroids (laparoscopic and transcervical approaches)

- MRI-guided focused ablation – shrinks fibroids

- Surgery

- Myomectomy – removal of fibroids (laparoscopic, robotic, abdominal, and hysteroscopic approaches)

- Reducing the risks over which you have control.

Studies have shown Black women are less likely to be treated for fibroids. And they have a higher rate (2-3 times higher than white women) of hysterectomy as well as less access to less invasive approaches to surgery, such as minimally invasive, laparoscopic, robotic, and vaginal techniques.

Therefore, Black women+ often have a longer hospital stay and recovery time and greater likelihood of complications.

And don’t forget hysterectomy can increase the risk of early menopause, even if your ovaries are not removed. As a result, you are at greater risk for a host of physical and mental health conditions and for a longer period of time over the course of your life.

It’s always important to advocate for the care you need and deserve, and this is one example of the need to make sure your symptoms are addressed and that you are told about the pros and cons for all the options available.

Addressing health disparities takes systemic change. If there’s ever been a time in your life to do something about it, menopause is an area with great potential for having an impact.

Black women have higher infant and maternal mortality rates (3-4 times higher)

than their white counterparts, even when educational level and socioeconomic status are the same.

Source: KFF

Higher infant and maternal mortality rates

In addition to menopause disparities, there are other increased gynecological risks for Black women, including higher infant and maternal mortality. And it often doesn’t matter who you are.

Even tennis superstar, Serena Williams, had to fight for her own life after giving birth – when she had pulmonary emboli as a complication and no one listened for hours, even though she had a previous history of blood clots.

So, how might your maternity history tie to your menopause journey? Certain complications during pregnancy can impact your health later in life, e.g., those who experience gestational diabetes are more likely to develop diabetes, higher risk of hypertension later if you have high blood pressure during a first pregnancy.

Studies have shown a risk of type 2 diabetes that is “32% higher in women who entered their menopause before 40 years of age compared with women having their menopause at 50-54 years.”

Women who develop hypertension during a first pregnancy have been found to be at greater risk of not only high blood pressure but also heart attack, heart failure, and stroke later in life. And Black women are more likely to develop hypertensive disorders during pregnancy than other groups.

39.2% of the Black community has prediabetes,

a condition in which your blood sugar (glucose) is higher than normal but not high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes.

12.1% of non-Hispanic Black adults in the U.S. have diabetes.

Diabetes

Diabetes occurs when your body cannot make (Type 1) or use (Type 2) insulin effectively. Insulin helps convert sugar (glucose) into energy for your body to use. So, when insulin is not made or used well, sugar builds up in your blood and organs. Insulin resistance occurs when cells in your muscles, fat, and liver don’t respond well to insulin and therefore it becomes difficult for them to take up glucose from your blood and use it for energy.

There is a range of sign and symptoms of diabetes. Among them are:

- frequent urination

- increased thirst and/or hunger

- blurred vision

- unintentional weight loss

- slow healing of cuts or bruises

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes include:

- family history

- gestational diabetes (diabetes during pregnancy)

- overweight/obesity

- metabolic syndrome

- high intake of sugar

- high intake of processed/ultra-processed foods

- sedentary lifestyle

- smoking

- stress

- exposure to racism

The Black community is more likely to experience complications from diabetes – eye issues and blindness, chronic kidney disease, neuropathy (tingling and/or numbness in the feet or hands), heart disease, and amputations.

Black women+ have a 63% greater risk than white women of developing diabetes later in life if they had new-onset diabetes in pregnancy.

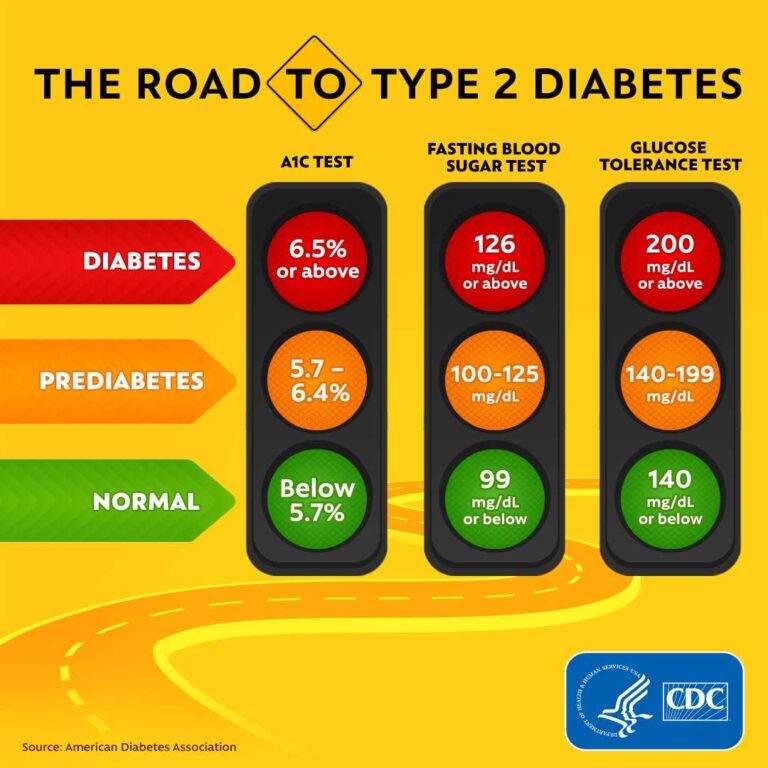

Courtesy: CDC

Why diabetes may be a health disparity for Black people

One factor which contributes to worse outcomes is a lower likelihood of receiving good-quality care according to guidelines, like:

- hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) testing (a measure of how well glucose has been controlled over the past 2 – 3 months)

- retinal (eye) exam

- cholesterol testing

Additionally, race has been used inappropriately with regard to certain lab testing, like how well the kidneys work – eGFR (glomerular filtration rate) – which has led to delayed diagnosis and treatment of kidney disease in the Black population. (And if a kidney transplant is needed, Black patients are less likely to receive one.)

It has also been found that a vitamin D deficiency can increase the risk of the type of eye disease seen in diabetes. And Black people are more likely to have severe vitamin D deficiency.

Screening and treatment

BMI is the most frequently used measurement of overweight/obesity and therefore as a predictor of insulin resistance.

However, when it comes to Black women+, a study found it’s more accurate to use:

- triglycerides (a type of fat)

- HDL (“good”) cholesterol

- triglyceride: HDL ratio

Learn more about diabetes treatment from the American Diabetes Association, and find out if you’re eligible for the CDC’s Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP).

And remember, living a healthy lifestyle (e.g., plant-based eating) to reduce the risk and mitigate the impact of diabetes will also help you manage menopausal symptoms during the journey too!

It's reported that as many as 4 in 5 Black women+ are overweight and obese.

Black women+ have the highest rates compared to any other group in the U.S., according to the CDC.

A word of caution on BMI measurements

The U.S. as a whole has a major struggle with overweight/obesity, with close to 75% of the overall adult population suffering from the conditions.

Although Black women+ have an alarming overweight/obesity rate (4/5), things may not be quite as dire as reported.

Here’s why! Body mass index (BMI) is the most commonly used measure of overweight/obesity. (BMI is weight divided by height squared.) It also assesses visceral body fat (internal fat that surrounds the organs and creates inflammation in the body), and, by extension, an increased risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes, gallstones, and certain cancers.

Unfortunately, BMI doesn’t take into account factors like age, sex, bone structure, muscle mass, and fat distribution, and therefore is flawed as a measure of body fat.

Consequently, its use to forecast risk for a variety of conditions can be faulty.

For those who are short, BMI can indicate greater “thinness,” while it might suggest greater “fatness” in those who are tall.

It also potentially disadvantages women, those who are athletes, the heavily muscled, those who are Black, Latino/Hispanic, those who are Asian stature with slight stature, and Indigenous Peoples.

Additionally, the Asian community has higher health risks at lower BMIs.

Health risks of obesity/overweight

Nonetheless, although there are better measures like waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio, the bottom line remains that there are health risks.

Overweight, obesity, and visceral fat have been identified as major causative factors for other conditions, as well as premature death (especially in women+ and Black adults), including:

- heart disease

- stroke

- hypertension

- type 2 diabetes

- osteoarthritis

- sleep apnea

- cancer (uterine/endometrial, breast, colon)

- high cholesterol and triglycerides

- metabolic syndrome

- dementia

Though often perceived by society as a lack of self-control and stigmatized in schools, healthcare settings, and the workplace, obesity is actually a complex and complicated disease.

Like many other conditions, there are risk factors that make it more likely, actions you can take relative to your lifestyle and habits to reduce those risks and manage your weight, and treatments that are effective.

Some risk factors of being overweight or obese include:

- Medical conditions like hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome, PCOS, metabolic syndrome, and depression.

- Genetics (The CDC reports that “Researchers have found at least 15 genes that influence obesity.”)

- Medications like certain antidepressants and antipsychotics, steroids to treat autoimmune conditions, and insulin (IF, glucose levels are not well controlled).

- Chronicall high-stress levels (which lead to high cortisol levels – the stress hormone – which leads to a negative impact on hormones that help regulate feelings of hunger and being full)

- Unhealthy lifestyle

- Marketing by the food and alcoholic beverage industries that is targeted to communities of color and other marginalized groups.

Managing your weight

So, what can you do? First, believe you do have the power to make a change for the better.

Then take action reinforced with a positive mindset, which has the extra added benefit of potentially reducing the severity of menopausal symptoms!

Next, focus on your lifestyle.

Avoid unhealthy eating habits

These include foods high in salt, sugar, and saturated fats like fast food and processed/ultra-processed food – and use “food as medicine.”

If you drink a lot of sugary beverages, start by switching to water, plain or infused with fruit. Sugary drinks have been noted to be a leading offender when it comes to overweight/obesity in the Black community as a whole.

Avoid fad diets that promise quick weight loss.

Not only can they be unhealthy and lead to nutritional deficiencies, dehydration, and fatigue, but they typically require changes that work in the short term but cannot be sustained over the long haul.

There are lots of other options that enable you to lose weight safely, effectively, and in a way you can realistically maintain. One example is the Mediterranean diet, which has been found to be “the best” overall eating pattern for 6 years in a row.

Engage in regular physical activity.

It’s best if your routine includes a (combination of cardio, weight training, flexibility, and balance). And avoid sitting for long periods of time. Sitting has been found to be as great a risk of premature death as having obesity. So, if you are already obese, the risk increases even more.

Physical movement in forms that are varied and that you enjoy will increase the likelihood of establishing a consistent routine. Some people find having someone to hold them accountable is very helpful. Learn about guideline recommendations here.Try to avoid taking an all-or-none approach. Some movement is better than no movement. Every little bit helps! For example, studies have shown the benefits of walking (or the equivalent of) begin at 2500 steps and the cardiovascular benefits are gained at 7000 steps a day. And remember, not getting in enough physical activity increases the risk of premature death by 20 – 30% compared to those who get in 30 minutes of moderate exercise most days of the week. And even 15-minute physical activity breaks have been shown to reduce the risk of premature death and death related to cardiovascular disease!

Learn coping techniques to manage stress.

This stage of life is a great time to explore various options you may not have tried in the past or have forgotten about, like the emotional freedom technique (EFT), aka tapping and mindfulness.

During the menopause journey, stress tends to be reported as a bigger component impacting day-to-day symptoms and quality of life by Black women, with being “… excessively burdened by physiological impacts of chronic stress caused by health disparities associated with chronic stressors, including perceived discrimination, neighborhood stress, daily stress, family stress, acculturative stress, environmental stress…”

Stress can also lead to disruption of the hormonal balance between ghrelin (increases your appetite) and leptin (decreases your appetite).

Be Less Stressed

Feeling stressed or overwhelmed? Learn life hacks to reduce stress with the Be Less Stressed toolkit.

"*" indicates required fields

Get enough, good-quality sleep.

You know how good it feels to wake up after getting enough, really good, yummy sleep! Between hot flashes, night sweats, emotional turmoil, feelings of anger or even rage, conditions like restless leg syndrome (RLS), the menopause journey can make that difficult. But there are things you can do to help:

- Establish a sleep routine.

- Try binaural beats.

- Explore cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can also help with hot flashes.

- Check out mind-body techniques.

Some potential treatment options

A healthy lifestyle is a key foundation for overall health, well-being, chronic disease and cancer risk reduction, and maintaining a healthy weight. Sometimes additional help is needed:

Structured weight loss program

Some people find it’s helpful in establishing new eating habits and getting support from others that can keep them motivated when things get challenging or their weight loss plateaus. Here are some tips for selecting one.

Bariatric surgery

is an option for some individuals. It’s important to recognize that it results in major changes in day-to-day life and that one must be mentally committed to new ways of eating. Otherwise, it is indeed possible to “out eat” the surgery and gain weight again. And remember being psychologically prepared is essential because it does not mean instant happiness.

Medications approved by the FDA

As of 2023 medications approved by the FDA for weight loss include:

- Phentermine-topiramate (Qsymia)

- Orlistat (Xenical, Alli)

- Bupropion-naltrexone (Contrave)

- Liraglutide (Saxenda)

- Semaglutide (Wegovy)

- Zepbound (tirzepatide)

- Setmelanotide (Imcivree)

Each medication has its benefits and risks, and it’s still key to maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Having a conversation with your healthcare practitioner is essential as you explore the best path to weight loss for your particular situation. For example, certain medications might be a better choice if you also have diabetes. Here are some tips to help you prepare for that conversation.

Black people are twice as likely to die from CVD than white individuals,

and Black women are two to three times more likely to die at a younger age from cardiovascular disease.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

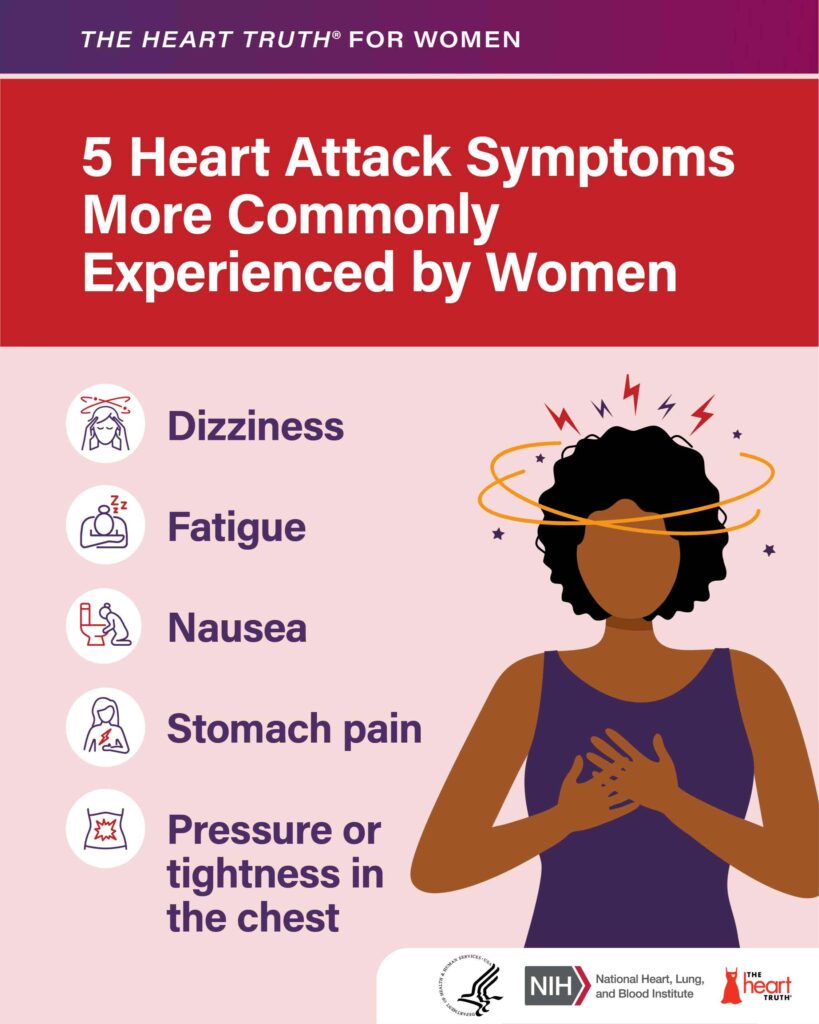

Cardiovascular disease includes conditions like heart disease, hypertension, and stroke.

Heart disease is the #1 killer of women in the U.S. And if you are a Black woman living in a rural area, you have the highest CVD death rate in the U.S.

Why is this? In general, Black women are at greater risk of several of many contributory factors:

- Hypertension (high blood pressure; seen in close to 60% of Black women)

- Hypertension during pregnancy

- Diabetes

- Abnormal lipid profile, specifically high LDL (“bad”) cholesterol) and low HDL (“good”) cholesterol

- Obesity

- Visceral fat (internal fat around the organs)

- Metabolic syndrome*

- Premature and early menopause

- Hot flashes

- Moderate-to-severe menopause symptoms

- Insomnia (due to menopausal symptoms)

- Hysterectomy

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which also increases the risk of metabolic syndrome

- Being subjected to racism (general and medical racism)

How is metabolic syndrome diagnosed?

* Metabolic syndrome is diagnosed if a person has at least three of the following five conditions:

- excess internal body fat around your organs with a waist circumference ≥ 35 inches in women+ (≥ 31.5 inches if you are Asian)

- high blood sugar (glucose)

- high blood pressure

- a high blood triglyceride (a type of fat that can increase your LDL “bad” cholesterol) level

- low HDL cholesterol (“good” ) level

Many of these heart disease risk factors are also connected across a spectrum of CVD conditions. For example, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome also increase the risk of stroke.

And Black women are more likely to have a stroke, to die from one, and to have a stroke at a younger age than any other racial group, with the impact of racism contributing significantly to the risk.

Learn more about hypertension, heart attack, and stroke.

In the U.S., African Americans have the shortest survival rates once diagnosed with cancer,

and the highest death rates from most cancers relative to other racial groups. And it is the 2nd leading cause (after heart disease) of death in Black women.

Cancer in the black population

Some of the reasons for the Black population (as a whole) for these abysmal cancer statistics are related to a greater likelihood of:

- Lower incomes

- Greater exposure to toxins/chemicals/air pollution

- Less access to healthy food (food desert)

- Greater concentration of and access to unhealthy food/fast food and alcohol stores in neighborhood (food swamp)

- Fewer physical activity resources

- Living in a redlined neighborhood

- Higher rates of obesity (a risk factor for cancer of the breast, colon, uterus, esophagus, kidney, gallbladder, liver, and pancreas), which is accountable for up to 8% of cancers in general

- Higher rates of stress

- Delayed diagnosis, delayed treatment, and treatment not aligned with treatment guidelines

- Less access to high-quality healthcare and health insurance

- Underrepresentation in clinical trials of cancer treatments

- Bias/discrimination/racism and their far-reaching impacts on health and well-being

Interestingly, recent Black immigrants to the U.S., who have had a differently lifestyle and experiences, tend to have a lower incidence of cancer.

Over the course of a lifetime, there is a 34% probability that a Black woman will develop cancer,

of which the most commonly diagnosed are breast, lung, and colorectum.

Cancer for black women+

Although Black women have an 8% lower incidence rate than white women, their cancer mortality rate is 12% higher.

Uterine cancer

Uterine cancer (aka endometrial cancer) rates are on the rise as are death rates. And the mortality rate for Black women is twice as high for those who are white.

Among the risk factors for uterine cancer are:

- Chemicals used in hair relaxants

- Personal history of breast or ovarian cancers

- A high-fat diet

- Using estrogen-only hormone therapy if your uterus is still intact

- Starting menstrual cycles at an age younger than 12

- Entering menopause later than the typical age (51 years old in the U.S. but it may be earlier in women of color)

- History of taking tamoxifen

- Prior pelvic radiation

- Being infertile or never having been pregnant

- Family history of Lynch Syndrome (genetic mutation which increases the risk of colon cancer, breast cancer, or ovarian cancer)

Unfortunately, there are currently no screening tests for uterine cancer, so it’s important to pay attention to your body and contact your clinician if you notice unusual vaginal bleeding, particularly if you are in the post-menopause stage of the journey.

Breast cancer

Black women+ are more likely to have a more aggressive form of cancer that is also less responsive to certain types of treatment (“triple-negative”) and have a higher mortality rate than white women. They also have a greater chance of getting inflammatory breast cancer, another aggressive form of the condition. Black women are also less likely to have access to the most current breast cancer screening technology.

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in Black women. However, there is good news. The death rate has actually declined (though not as much as for white women).

Breast cancer symptoms include:

- breast lump or mass

- Breast or nipple pain

- Nipple retraction (turning inwards) or discharge

- Skins changes on the breast such as reddening, thickening, dryness or flaking

- Breast swelling (full or partial)

- Swollen lymph nodes

Current guidelines with regard to screening, usually with a mammogram starting at age 40, is vitally important, as is connecting with your healthcare professional to determine the age, frequency, and method of screening indicated in your particular situation based on your personal risk factors.

In addition to race, risk factors include:

- Personal history of breast cancer

- Family history

- Unhealthy eating

- Physical inactivity

- Alcohol

- Getting your period at an earlier age

- Later age of onset of menopause

- Never being pregnant

- Not breastfeeding if you have a baby

- Being overweight/obese

- Some types of birth control

- Menopausal hormone therapy (some types in some women)

- Genetic mutations – BRCA, STK11, PALB2, CDH1, TP53, CHEK2, PTEN

- Dense breasts

- Radiation to the chest

- Exposure to DES

Here is a resource to help you navigate a breast cancer journey.

Lung cancer

The most common cause of lung cancer is smoking, and rates have been on the decline. Thankfully, in a related way, lung cancer rates and deaths have also fallen significantly. And Black women actually have a lower rate of lung cancer than white women.

However, it’s important to note that up to 20.8% of women+ in general who are diagnosed with lung cancer have never smoked! Other risk factors include second-hand smoke and exposure to air pollution, radon gas, asbestos, arsenic, uranium, and diesel exhaust. It also appears some never-smokers have a different type of lung cancer.

Colorectal cancer (CRC)

After, Indigenous Peoples in the U.S., Black people have the second highest rate of CRC. It is the third most common cancer and third most common cause of cancer-related death in Black women.

As screening rates have increased and vitamin D deficiency has been identified as a potential risk factor, health disparities have decreased. And because the majority of colon cancer begin in a certain type of polyp (adenomatous), early detection is possible and affords the possibility of catching things sooner or maybe avoiding colon cancer altogether.

Unfortunately, a new trend has emerged globally with the fastest rising rates of colon cancer and colon cancer-related deaths now found in people younger than 50. Common symptoms in this group include rectal bleeding, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and iron deficiency anemia. (These are common signs of CRC in general, and other symptoms include a change in bowel habits, a feeling of incomplete bowel movements, and unintentional weight loss.)

It is also still the case that Black people are more likely to have delayed treatment and less likely to receive recommended surgery, chemo, and/or radiation therapy when they do get treatment. They also have a greater chance of having a cancer on the right side of the colon, which tends to have less favorable outcomes.

Risk factors for CRC include:

- Overweight/obesity

- Alcohol consumption

- A high-fat, low fiber diet

- Processed meats

- Physical inactivity

- Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis)

- Having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Family history of Lynch Syndrome (genetic mutation which increases the risk of colon cancer, breast cancer, or ovarian cancer)

- Tobacco use

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s is the most common type of dementia in the U.S., accounting for 60 – 80% of people with dementia.

In Alzheimer’s disease there is damage to the brain from clumps (beta-amyloid) and tangles in the brain (tau protein). (Another common cause is cerebrovascular disease and is called vascular dementia. It occurs in up to 10% of people with dementia and is caused by damage to the blood vessels that provide oxygen and nutrients to the brain.)

Changes in the brain often begin up to 20 years before symptoms like the following appear:

- Memory loss (recent events, names, etc.)

- Problems with concentration

- Confusion

- Communication issues

- Personality/behavioral changes

- Wandering

- Difficulty in walking, swallowing, and speaking

Alzheimer’s is more prevalent in women and in Black people. So, Black women have a double whammy, as well as a greater likelihood of late-onset disease.

Risk factors include:

- Older age

- Family history

- Overweight/obesity

- High blood pressure

- Cardiovascular disease

- Diabetes

- High LDL (“bad”) cholesterol

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Unhealthy eating habits

- Vitamin deficiencies – folate, vitamins D, B6, and B12

- Alcohol consumption

- Smoking

- Sleep apnea

- Hearing loss

- Air pollution

- Brain changes related to chronic stress from racism lead to weathering and earlier brain aging

- Head trauma

- Having Down’s syndrome

It’s important for you to get a thorough work-up to make sure you actually have Alzheimer’s, for which there is a genetic component and, therefore, implications for family members, and not another form of dementia. It can make a difference in the type of treatment that is appropriate and also help to ensure symptoms are not related to other things which can be addressed and resolve your symptoms. Possibilities include:

- Thyroid conditions

- Electrolyte imbalances

- Vitamin B1, B12, E, or copper deficiencies

- Medication

- A brain tumor

- A subdural brain bleed (bleed between the surface of the brain and the covering over the brain) after a fall

- Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (buildup of fluid in the cavities in the brain)

Learn more about Alzheimer’s and other dementias here.

Doctors need to change Black woman’s care for the better

Several obstetricians and gynecologists spoke out about the stark differences in women’s health in “Black Lives Matter: Claiming a Space for Evidence-Based Outrage in Obstetrics and Gynecology.”

“Enough is enough. Race is a social construct, and the overwhelming statistics we present are attributable to a broken racist system, not a broken group of women.

Evidence-based outrage is the objective, logical conclusion. We, as the caretakers of women’s health, must realize that real action requires enough courage to embrace a fundamental shift in our perspective.

We challenge obstetricians–gynecologists to consider how accepting that Black women do worse in your research study, worse in your quality improvement project, or are absent from your clinical trial as the status quo directly reinforces the lesser value our society has assigned to Black women’s lives.

Instead of sitting back on the reflexive defense that racial disparities are too complex for us to do anything about, what if we decided to try anyway? What if every obstetrics and gynecology department made racial equity in known areas of disparity the priority of all quality improvement projects?”

Dr. Makeba Williams is Associate Professor and Vice Chair of Professional Development and Wellness in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Washington University’s School of Medicine. She reviewed the medical literature and found Black Women experience differences in physical, psychological, social, and quality of life measures during the menopause journey compared to white women. Based on her review of 20 years of medical literature (of which she found only 17 academic papers explored how the menopause journey affects Black women), she has published findings which detail the health disparities and root causes of these differences, which also impact the care and treatment they receive. Stay tuned!

As we’ve discussed, there are many health disparities which exist for Black women+ in addition to their symptoms and experiences during the menopause journey.

Addressing health disparities takes systemic change. And it can be discouraging if you find yourself unfairly disadvantaged when it comes to your health and well-being (and other aspects of life). But you’ve made it thus far against all odds across generations. You do have what it takes to keep moving forward, both for yourself and those who follow!

If there’s ever been a time in your life to do something about it, this stage of life is one with great potential for having a life-changing impact.

Resources

- Blackdoctor.org

- Black Girl in Om®

- Black Women’s Health Imperative

- Health in Her Hue

- The Loveland Foundation

- Office on Women’s Health

- Office of Minority Health

- NAMI

- Therapy for Black Girls

- Migration Meals: How African American Food Transformed the Taste of America

- American Heart Association

- What Every Black Woman Should Know About Heart Disease

- Factors Impacting Women’s Cardiovascular Health Across the Lifespan

- DASH Diet (for hypertension)

- American Cancer Society

Free Support

For Your Menopause Journey!

Only available for a limited time!

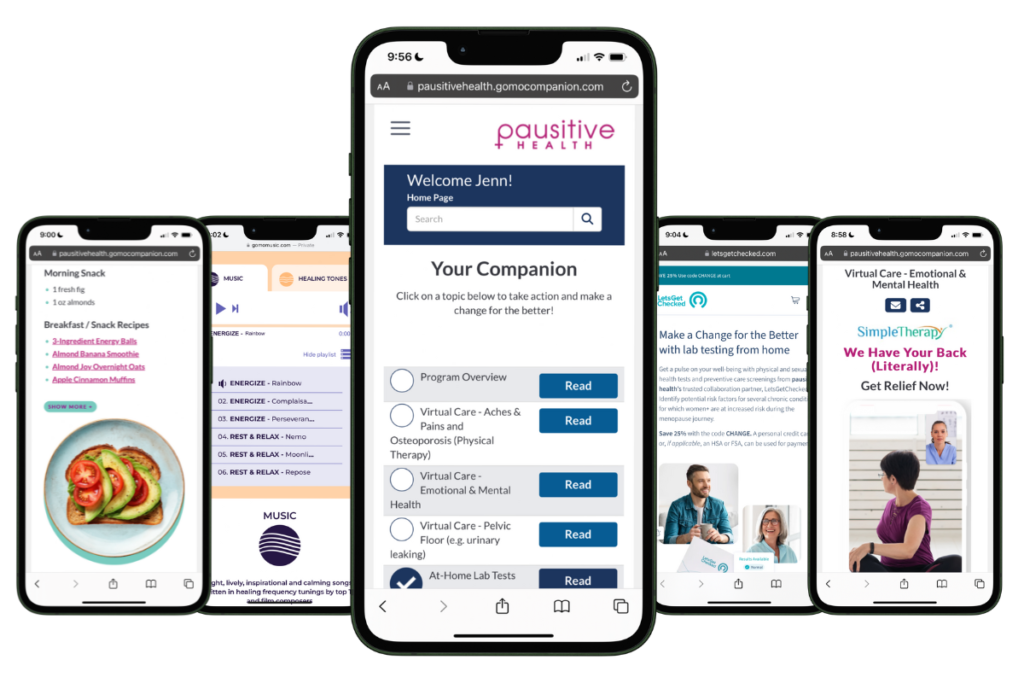

Access a one-stop menopause journey digital destination that provides personalized text messages that focus on educational topics you select and offers many other features such as a diet assessment with recommendations, solutions from collaboration partners to address menopausal aches and pains (the musculoskeletal syndrome of menopause – MSM), pelvic floor issues, virtual care, lifestyle tools, and a supportive community.

The Growing Diversity of Black America | Pew Research Center

Uncovering drivers of racial disparities in uterine fibroids and endometriosis | Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation

Edwards TL, Giri A, Hellwege JN, Hartmann KE, Stewart EA, Jeff JM, Bray MJ, Pendergrass SA, Torstenson ES, Keaton JM, Jones SH, Gogoi RP, Kuivaniemi H, Jackson KL, Kho AN, Kullo IJ, McCarty CA, Im HK, Pacheco JA, Pathak J, Williams MS, Tromp G, Kenny EE, Peissig PL, Denny JC, Roden DM, Velez Edwards DR. A Trans-Ethnic Genome-Wide Association Study of Uterine Fibroids. Front Genet. 2019 Jun 12;10:511. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00511. PMID: 31249589; PMCID: PMC6582231.

Pavone D, Clemenza S, Sorbi F, Fambrini M, Petraglia F. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Uterine Fibroids. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. January 2018. Volume 46, Pages 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.09.004

Science Update: Study identifies potential contributor to racial disparities in uterine fibroid disease | National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Baranov VS, Osinovskaya NS, Yarmolinskaya MI. Pathogenomics of Uterine Fibroids Development. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Dec 6;20(24):6151. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246151. PMID: 31817606; PMCID: PMC6940759.

Qin H, Lin Z, Vásquez E, Xu L. The association between chronic psychological stress and uterine fibroids risk: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Stress Health. 2019 Dec;35(5):585-594. doi: 10.1002/smi.2895. Epub 2019 Sep 5. PMID: 31452302.

Qin H. Lin Z, Vásquez E, Luan X. High soy isoflavone or soy-based food intake during infancy and in adulthood is associated with an increased risk of uterine fibroids in premenopausal women: a meta-analysis. Nutrition Research. 71(40). June 2019

Eltoukhi HM, Modi MN, Weston M, Armstrong AY, Stewart EA. The health disparities of uterine fibroid tumors for African American women: a public health issue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;210(3):194-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.008. Epub 2013 Aug 11. PMID: 23942040; PMCID: PMC3874080.

Wieslander CK, Grimes CL, Balk EM, Hobson DTG, Ringel NE, Sanses TVD, Singh R, Richardson ML, Lipetskaia L, Gupta A, White AB, Orejuela F, Meriwether K, Antosh DD. Health Care Disparities in Patients Undergoing Hysterectomy for Benign Indications: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Nov 1;142(5):1044-1054. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005389. PMID: 37826848.

Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them | KFF

What Serena Williams’s scary childbirth story says about medical treatment of black women | Vox

Brand JS, van der Schouw YT, Onland-Moret NC, Sharp SJ, Ong KK, Khaw KT, Ardanaz E, Amiano P, Boeing H, Chirlaque MD, Clavel-Chapelon F, Crowe FL, de Lauzon-Guillain B, Duell EJ, Fagherazzi G, Franks PW, Grioni S, Groop LC, Kaaks R, Key TJ, Nilsson PM, Overvad K, Palli D, Panico S, Quirós JR, Rolandsson O, Sacerdote C, Sánchez MJ, Slimani N, Teucher B, Tjonneland A, Tumino R, van der A DL, Feskens EJ, Langenberg C, Forouhi NG, Riboli E, Wareham NJ; InterAct Consortium. Age at menopause, reproductive life span, and type 2 diabetes risk: results from the EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetes Care. 2013 Apr;36(4):1012-9. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1020. Epub 2012 Dec 10. PMID: 23230098; PMCID: PMC3609516.

Mureddu GF. How much does hypertension in pregnancy affect the risk of future cardiovascular events? Eur Heart J Suppl. 2023 Apr 21;25(Suppl B):B111-B113. doi: 10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suad085. PMID: 37091660; PMCID: PMC10120948.

Minhas A, Ogunwole S M, Vaught A, Wu P, Mamas M, Gulati M, Zhao D, Hays A, and Michos E. Racial Disparities in Cardiovascular Complications with Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension in the United States. Hypertension. 2021;78:480-488. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17104

Statistics About Diabetes | American Diabetes Association

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 1 January 2024; 47 (Supplement_1): S20–S42. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S002

Take the Type 2 Risk Test | American Diabetes Association

Preventing Type 2 Diabetes with the Lifestyle Change Program | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Haw JS, Shah M, Turbow S, Egeolu M, Umpierrez G. Diabetes Complications in Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the USA. Curr Diab Rep. 2021 Jan 9;21(1):2. doi: 10.1007/s11892-020-01369-x. PMID: 33420878; PMCID: PMC7935471.

Bower JK, Butler BN, Bose-Brill S, Kue J, Wassel CL. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Diabetes Screening and Hyperglycemia Among US Women After Gestational Diabetes. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:190144. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.190144

Testing for Diabetes | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Haw JS, Shah M, Turbow S, Egeolu M, Umpierrez G. Diabetes Complications in Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the USA. Curr Diab Rep. 2021 Jan 9;21(1):2. doi: 10.1007/s11892-020-01369-x. PMID: 33420878; PMCID: PMC7935471.

Uppal P, Golden BL, Panicker A, Khan OA, Burday MJ. The Case Against Race-Based GFR. Dela J Public Health. 2022 Aug 31;8(3):86-89. doi: 10.32481/djph.2022.08.014. PMID: 36177174; PMCID: PMC9495470.

El-Khoury B, Yang TC. Reviewing Racial Disparities in Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: a Socioecological Approach. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023 Mar 29:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40615-023-01573-x. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36991297; PMCID: PMC10057682.

Zahedi M, Mehdi Motahari M, Fakhri F, Moeini Aphshari N, Poursharif S, Jahed R, Nikpayam O. Is Vitamin D deficiency associated with retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus? A case-control study. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. February 2024. Volume 59, Pages 158-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.11.011

Find a Culturally Sensitive Doctor | BlackDoctor

Home | Black Girl In OM

Home | Black Women’s Health Imperative

Provider Directory | Health in Her Hue™

Loveland Therapy Fund | Loveland Foundation

Home | Office on Women’s Health

Home | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health

NAMI’s Statement on Recent Racist Incidents and Mental Health Resources for African Americans | National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

Home | Therapy for Black Girls

Migration Meals: How African American Food Transformed the Taste of America | EatingWell

Home | American Heart Association

What Every Black Woman Should Know About Heart Disease | BlackDoctor, Inc.

Factors Impacting Women’s Cardiovascular Health Across the Lifespan | Society for Women’s Health

DASH Eating Plan | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Home | American Cancer Society

Black Women and Menopause: Why Symptoms Can Be Longer and More Severe

As a Black woman, menopause symptoms, including hot flashes, can be longer and more severe. Learn why and what you can do.

5 Ways Medical Gaslighting Can Make Your Menopause Journey More Difficult

Do you feel like your doctor dismisses your menopause symptoms? Medical gaslighting can leave you feeling crazy and make menopause harder.

15 Causes Of Premature Or Early Menopause: Could It Happen To You?

Premature is when menopause happens before age 40 and early menopause is after age 40 but before age 45. Learn about the causes of premature and early menopause and why it matters for your health.